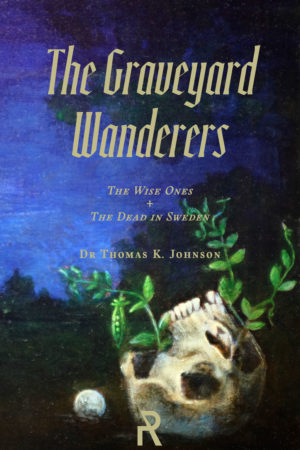

A Similitude of Nature

Giorgio Anselmi on the Images of the Eighth Celestial Sphere

An Edition and Translation of Material from the Divinum Opus de Magia Disciplina

translated by Brian Johnson

208 pages / softcover B&w / 12 May 2025 / 9781947544659

Astrological images, so 15th-century astrologer Giorgio Anselmi notes, are not limited to the narrow band of zodiacal stars. In A Similitude of Nature, translator Brian Johnson reintroduces us to the layer of magical meaning hidden in the eighth celestial sphere. Anselmi unpacks new layers of magic possible when we step beyond the Behenians and into a larger scope of environmental awareness of the celestial firmament. Revelore presents this work alongside the original Latin for those enterprising scholar mages who seek to work with the original treatise by Anselmi.

This text is an essential addition to the reference shelf of any practicing celestial magician.

For those who wish to purchase from Europe, please inquire with your local bookshop and have them write our wholesale dept., or visit the Celestial Arts Education Library’s AbeBooks portal after the official release date.

Contents

Introduction

I. Tractate Four: On the Methods of Characters, and Examples Thereof.

Chapter One: A Note on the Methods which Are to Be Observed in the Composition of Images.

Chapter Two: In What Materials Images and the Like Are to Be Imprinted.

Chapter Five: The Manners of Images Found in Certain Gemstones, and Their Powers.

II. The Fourth Part of the Fourth Tractate of George of Parma, on the Specific Methods Pertaining to the Images of the Eighth Sphere, and on the Methods of their Composition, by Means of Examples.

Chapter One: On the Images which Are Made According to the Twelve Signs of the Zodiac.

The image of Aries

The image of Taurus

The image of Gemini

The image of Cancer

The image of Leo

The image of Virgo

The image of Libra

The image of Scorpio

The image of Sagittarius

The image of Capricorn

The image of Aquarius

The image of Pisces

Chapter Two: A Note on the Methods of Composing the Images of the Eighth Sphere That Lie North of the Zodiac.

-

-

- Ursus Major

- Ursus Minor

- Draco

- Cepheus

- Boötes

- Corona Borealis

- al-Rāqeṣ

- Lyra

- Cassiopeia

- Caput Algol

- Auriga

- Ophiuchus

- Sagitta

- Aquila

- (Cygnus)

- Delphinus

- Equuleus and Pegasus

- Andromeda

- Triangulum

-

Chapter Three: A Note on the Methods Pertaining to Those Images Made Under the Stars of Those Figures Which Occupy the Region South of the Zodiac.

-

-

- Cetus

- Orion.

- Eridanus

- Lepus

- Canis Major

- Canis Minor

- Hydra

- Corvus

- Argo Navis

- Centaurus

- Lupus

- (Ara)

- Corona Australis

-

Chapter Four: On the Methods of Composing Images which Are Not Stellar, but Accompany the Twelve Signs.

– to cure cholera, and pains of the stomach, and to preserve one from these

– to prevent a bandit from entering a house

– so that fire should not ignite in a house

– so that neither serpents nor reptiles shall obstruct a place, but flee and die

– to make demons disturb, agitate, harass, and vex

– to gather together, and multiply, and make fortunate goats, and sheep, and creatures of this sort

– so that enemies neither can nor dare to enter a city or place, either by force or deception

– to render all locks ready to be opened

– so that a dog will not come toward nor bark at a person

– so that a horse is halted, (so as) not to pass through where the image is sculpted

– so that no animal shall be made to halt, but rather will flee a place as though struck by a whip

– so that every ass … shall halt, and, relieved of its burden, bray

– to cause all the cattle and bulls … to stop and bellow

– so that beasts congregate

– so that birds to congregate in the place where it is kept, especially ravens

– so that domestic birds and hens congregate in some place and sing

– to make fish flee from a lake or river

– to prevent a field from being cultivated

– so that goods shall not be sold, either by weight or by quantity

– so that, cast into the water of a spring or flowing cistern, the waters [halt and …] dry up completely

– so that all instruments may be bound, and destroyed, and broken

– so that worms shall gnaw the roots growing in the soil, and whatsoever is fit to be gnawed

– so that a bow or ballista will not shoot, or otherwise will break

– for inciting [people] to anger, and making them recalcitrant

– so that people will cry out and raise their hands

– so that people will sing

– so that people will place their clothes on the ground and lie upon them

– so that women will sing, and comb and scratch their heads

– so that the inhabitants [of a house or inn] shall not stop eating, nor can they be satisfied

– so that women will sing

– so that a woman will go and return to the same place repeatedly

Bibliography

Colophon

Introduction

by Brian Johnson

The early decades of the fifteenth century found the practice of astrological image magic in something of a transitional phase within Latin Christendom. Thanks in part to Arabic philosophical and magical works which had begun arriving in the twelfth century, and the charitably broad-minded reception thereof by scholars such as Adelard of Bath, William of Auvergne, and others,[1] the practical science of stellar influences had long since been liberated from the unequivocal judgment—if not the lingering suspicion—that it was merely a mask of propriety under which demons might manipulate the naïve. By the end of the Middle Ages, the prescription of talismans crafted according to the observation of propitious astrological conditions was recognized as a valid form of medical intervention, suitable for no less a patient than the pope himself.[2]

But if astrological images were, in principle, licit, the criteria circumscribing what was permissible in their construction, as well as the learned understanding of by precisely what means they operated, remained in flux. It was not (quite) yet time for Marsilio Ficino’s De vita libri tres, with its Platonically-informed theory of a cosmic spiritus susceptible to attraction by appropriately prepared materials and harmonious musics,[3] to say nothing of an astrological optics like that espoused later still by John Dee in his Propaedeumata aphoristica.[4] There was, however, another such doctor-astrologer who was prepared to step into this atmosphere of intellectual ferment in order to promulgate his own synthetic methodology for composing images, one in which “only the present disposition of the heavens is considered”—but the role of mediating intelligences remains as opaque as ever.

Giorgius Parmensis

Born in the city of Parma, at that time part of the Duchy of Milan, presumably not many years before the death of his father in 1386, Giorgio Anselmi was a student and theoretician of the natural sciences, music, and—insofar as can be judged from one of his scant few surviving works, the Divinum opus de magia disciplina—magic, of both the natural and demonic varieties. He studied the arts and medicine at Pavia, and was admitted to the faculty of the University of Parma upon its reestablishment in 1412.[5] He was involved in reforming the statutes of the college of physicians there in 1440, and the last we hear of him—short of a somewhat disparaging assessment by Agrippa half a century later[6]—is in the year 1448/9, teaching practical medicine at the University of Bologna.[7] In the intervening years he wrote at least three treatises: an Astronomia, preserved in an undated, composite copy,[8] on the nature and motion of the heavenly bodies and their influence upon earthly things; De musica, the single extant copy of which is dated 1434,[9] on celestial, instrumental, and vocal music theory; and the Divinum opus de magia disciplina.[10] The Divinum opus, after a summary definition of magic and its divisions, proceeds to systematically examine several forms of divination, demons and the procedures for conjuring them, magical images which harness the power of their stellar counterparts according to principles of natural similitude, and finally a (seemingly incomplete) discussion of methods for directly influencing living bodies, which gets no farther than veneficiis. Like Anselmi’s other known works, the Divinum opus exists in only one more or less complete manuscript copy, currently held by the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence, Italy.[11] The copyist (and textual integrity) of this manuscript appears to change abruptly between folios 157v and 158r, and it is undated. However, this version of the text is supported by a separate, partial copy at the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, dated 1542 and containing only the fourth part of the fourth tractate,[12] on the images of the eighth celestial sphere, corresponding to folios 196r–224r in the Florence manuscript.

Natural Magic and Celestial Instruments

The general paradigm within which Anselmi’s exposition of astral images unfolds is the Ptolemaic-Aristotelian scholasticism of his university curriculum. The changeable things of the sublunary elemental world are subject to movement by prior efficient causes—general ones affecting generic classes of things, or the condition of things in general across spans of time and space, particular ones predicating particular individual cases—and those causes include extraterrestrial bodies like the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars.[13] It is precisely in terms of general causes and effects that Anselmi explains the operation of his own images, based as they are upon that outermost and hence most general of celestial causes (short of the primum mobile and empyrean), the sphere of the fixed stars.[14]

Thus, by virtue of their inherent powers and motions, the perfect, impassible heavens work in a basically mechanistic way upon earthly things of corresponding natures;[15] a gemstone, for instance, carefully selected for its Jupiterian qualities and engraved with an appropriate talismanic image, would necessarily move in sympathy with the benefic actuations of the planet Jupiter. The nature of this correspondence or sympathy can be understood in terms of certain occult properties shared by individual substances participating in a specific form which they hold in common, an accepted principle of medical science by the fourteenth century.[16] Indeed, Albert the Great in his book De mineralibus had explained the marvelous powers inherent in precious stones as a function of just such specific forms, each of which mediates “between…the heavenly powers by which it is conferred, and the matter of the combination into which it is infused.”[17] Anselmi’s own conception of such formal similarity between that which is above and that which lies below may have derived, at least partly, from a Platonist belief that all of creation is informed by consonant series of numerical ratios, embodied in the tones produced by heavenly cycles and epicycles no less than in the workings of the human soul, a vision of cosmic harmony he espoused more explicitly in the De musica.[18]

The celestial bodies, in themselves, are devoid of manifest elemental qualities, and so those sublunary beings and contingencies to which particular planets or constellations correspond can be known only by inference born of long-observed correlations of motion and activity.[19] Anselmi was an empiricist; commenting upon the “marvelous virtues and abilities” which minerals possess due to their harmony with “the movement and power and nature of the sphere above,” he credits human knowledge of such coordinations between the celestial and terrestrial to observant investigation, presided over by “mistress experience.”[20] And while he concedes that astrologically elected images may not in fact be able to manifest their powers perpetually or eternally, given the ever-fluctuating state of the heavens, or to do so indifferently for each and every patient, he defends their capacity to retain such “great and famous properties” in principle based upon his own observation of experiments to that effect.[21]

This was all fairly uncontroversial in Anselmi’s time. Already in the thirteenth century, the Speculum astronomiae—an anonymous apologia for astrological studies likely penned by Albert himself[22]—had argued that “…if God…has ordered this world in such a manner, that He…should wish to operate through the created things found in these four inferior elements, using the mute and deaf stars as if they were instruments…what could be more desirable to a thinking man than to have a middle science which might teach us how this and that change in the mundane world is effected by the changes in the celestial bodies?”[23]

This cosmology was not a strictly materialist one, however. Aristotle attributed to the celestial spheres a principle of motion not essentially different from his first principle, the immaterial unmoved mover,[24] and elsewhere he described them in terms which could be construed as imputing a soul (ἔμψυχος).[25] Later interpretations differed as to whether this “soul” were rational or merely a principle of motion, but by the end of the thirteenth century the understanding espoused by authorities including Thomas Aquinas and Albert was that the movers of the heavenly spheres were indeed rational, though even these doctors of the church remained ambivalent as to whether they could properly be called angels.[26]

But if there were even potentially room for angels in the chain of astral-terrestrial causality, there was certainly room for demons. Albert accepted the proposition that demons could manipulate or appropriate the influences of celestial bodies for their own ends, though they themselves remained bound beneath the heavens,[27] and Michael Scot went so far as to suggest that at least some of the constellations’ influence in the sublunary world was ultimately demonic in origin.[28] Anselmi, for his part, while attributing the generation and corruption of changeable elemental bodies to their natural inclination to follow the movements of the heavens according to principles of likeness,[29] in some places implies that angels, or perhaps demons, are in fact the proximate movers of those sublunary things, albeit in accordance with the guiding forms embodied by the stars.[30] Indeed, the precise mechanism by which Anselmi understood the motive force of the stars to find its way to the realm of elemental bodies remains rather vague in the Divinum opus. We find no explicit reference to the theory of multiplication of species, à la Roger Bacon, or to the rays of al-Kindi, though either or both could easily have been tacitly assumed in a scientific text of the fifteenth century, and nothing in the opus seems to preclude them as explanations. The most that Anselmi leaves us with is a brief allusion to the operation of magnets by way of a general analogy to sympathetic action at a distance; still, for one so musically-minded, perhaps it was after all simply a matter of vibrations, like resonance in the harmonically tuned strings of a lute.

Another ambiguity lies in his use of both tropical and sidereal frames of reference. On one hand, Anselmi clearly distinguishes between the Zodiac signs and their corresponding constellations. He locates particular stars of the latter in terms of their place beneath a given degree of the tropical ecliptic,[31] itself divided into the traditional houses,[32] and even makes reference to the historically observable phenomenon of precession.[33] At times, however, his terminology appears ambivalent, as though he has not fully harmonized the language of some older sources which did not recognize such a distinction; reference is made to the luminaries moving under a zodiacal image (Anselmi’s usual term for a constellation) in one place, under a sign in another,[34] for instance. Granted, it is the influence of the constellations—the stars themselves—with which Anselmi is primarily concerned here. For while he allows that “each one of the signs of the Zodiac governs the things of this world below,” so too do “the remaining images” which “accompany the twelve signs of the Zodiac,” in the same way as “the remaining stellar images, thirty-six in number, which are depicted outside the Zodiac.”[35]

In both his theoretical perspective and the specific examples he formulates, Anselmi seems to present a novel, and not always fully articulated, synthesis of various sources and explanations for the mechanics of magic. Not only in his juxtaposing of chapters on exorcistic ceremonies with those pertaining to a more naturalistic sort of image magic, but within the discourse of those respective subdivisions themselves, Anselmi neither entirely distinguishes “natural” from “demonic” magic, nor consistently represents the role of spiritual agents—or other bodiless entities, like the heavenly signs—in the processes of nature, including the operation of magical images. Yet, if nothing else, Anselmi appears to have maintained a relatively unvarying cosmological viewpoint throughout his oeuvre, as the secondary causal role he imputes to spirits in the Divinum opus is precisely what we find in his Astronomia as well.[36]

Parallels and Precedents, or the Lack Thereof

Anselmi’s treatment of magical images, with which the present volume is primarily concerned, appears to be largely in agreement with, if not directly informed by, the philosophical authorities of his age, and no less uncomfortably poised between licit natural science and the forbidden invocation of demons. The eleventh chapter of Albert’s Speculum is devoted to his own attempt at drawing just such a distinction, and comes down in favor of a method for constructing purely “…astronomical images, which eliminates the filth, does not have suffumigations or invocations and does not allow exorcisms or the inscription of characters, but obtains [its] virtue solely from the celestial figure….”[37] Albert attributes his explanation for the efficacy of such images to the ninth sentence of (pseudo-)Ptolemy’s Centiloquium,[38] and Caroti et al. have demonstrated that the worked example of an image which Albert provides likely bears a direct debt to the De imaginibus of Thabit ibn Qurra.[39] Albert’s discrimination of exorcistic from strictly celestial talismans, while drawing distinctions which cut across those categories quite differently from the ones Anselmi adumbrates, certainly provided a model for later taxonomies, including the Parmense’s own delineation of the “ceremonial” and “natural” methods of composing images,[40] although Anselmi withholds the explicit moral judgment which is rather the entire point of Albert’s treatise.

A chronological intermediary between the Speculum and the Divinum opus—and perhaps a direct source for Anselmi’s articulation of an image magic which might be either astrological, demonic, or a bit of both—is the De occultis et manifestis of Antonio da Montolmo. Antonio lectured on grammar, medicine, and astrology at the University of Bologna nearly a century prior to the time that Anselmi was teaching there, but it is not implausible that the latter could have encountered a copy of his treatise still in circulation amongst the faculty. The fourth chapter of Antonio’s work exactly predicts Anselmi’s in the three methodologies it posits for empowering talismanic objects, as well as in the observation that such workings are most effective when a conducive ordering of the heavens is combined with aid from spiritual assistants persuaded by words and suffumigations.[41]

Nonetheless, where Anselmi’s instructions do recommend any sort of verbal utterance on the part of the artificer, this is always of a purely optative nature, “so that the power of the artificer may fall upon” the work,[42] never an imperative that might potentially be construed as addressing another rational being—with the possible exception of one image which is crafted for the explicit purpose of calling upon a demon to harass a victim.[43] In any case, the Divinum opus demonstrates that by the early fifteenth century, at least some practitioners were reflecting upon, if not thoroughly embracing, the Speculum’s program for a sanitized astral magic.

While in some cases Anselmi’s sources for the Divinum opus can be identified with a fair degree of confidence,[44] in others, such as the astral images of the fourth tractate, things are less certain. The De imaginibus of Thabit can only be compared to Anselmi’s work in general terms.[45] Thabit’s selection of experiments is more limited in scope, and rather more open-ended in its instructions, given that each posited image requires a unique election, keyed to the ascendant—whether natal, horary, or generic—of the specific subject or inquiry to which it pertains. Anselmi’s images, by contrast, make use of fairly rote celestial arrangements, intended to be capable of influencing whole classes of individual things and circumstances ruled over by various signs and asterisms, though he also addresses such relatively complex techniques as primary direction of the natal chart, considering their implications for determining the proper zodiacal talisman to utilize at a particular time in a patient’s life.[46] Again, where the Divinum opus prescribes at least broad guidelines for the sort of materials in which it would be most apt to craft a given image, namely those corresponding in their nature to the desired qualities of the primary celestial body dictating the hour of its election[47]—most often the Sun or Moon in Anselmi’s examples—De imaginibus is seemingly indifferent to the question of material basis, stating more than once that the artificer should simply use “whatever [metal] you wish.”[48] While Anselmi may indeed have referred to De imaginibus, known in its Latin form since the twelfth century,[49] in formulating his practical methodology, Anselmi’s images, no less than those of Thabit, are constructed from astrological first principles, and are perhaps of his own derivation.

A text bearing a greater similarity to Anselmi’s, at least in its formal structure, is another book “on images,” this one first appearing in Latin in book II, chapter 12 of the Picatrix where it is attributed to Hermes, and which was copied repeatedly down through the sixteenth century.[50] Anselmi’s chapter “On the Images Which Are Made According to the Twelve Signs of the Zodiac” may represent a further evolution of this Hermetic tradition, as both texts are organized around the twelve signs of the Zodiac, their instructions focused upon the proper disposition of the benefics, malefics, Sun, Moon, and Mercury, as well as the proper planetary hours for working; moreover, a number of the images clearly derive from a common source. However, the specific electional prescriptions in the two texts are entirely different, with Hermes giving consideration to the signs’ decan divisions, and more negative injunctions as to where or in what condition a given celestial body should not be, whereas Anselmi’s prescriptions are more direct, stipulating relative aspects and sometimes degrees of exaltation.

One final source which also undoubtedly shares a genealogy with some of the examples given in the Divinum opus is the pseudo-Ptolemaic De imaginibus super facies signorum. Like the Hermetic text just mentioned, this one too is organized around a sequential progression through the signs, noting in particular the rising decan under which each of its images should be made.[51] The prescribed forms and intended effects of at least some of these images appear to closely correspond to certain of those images which Anselmi says “are not stellar, but accompany the twelve signs”,[52] yet Anselmi (or his proximate source) largely refrains from any discussion of explicit decan placements, and instead correlates this selection of talismans to the Moon’s co-ascension with various zodiacal and extra-zodiacal stars. While it also entered the Latin milieu through a translation from the Arabic, the De imaginibus of pseudo-Ptolemy survives in a significantly greater number of manuscripts than the text credited to Hermes;[53] however, as far as I am aware, Anselmi’s apparent reception and reworking of either of these texts has heretofore gone unremarked in the scholarship. Anselmi’s familiarity with sources indebted to Arabic astronomical science is further demonstrated by his inclusion of a number of constellation and star names which are clearly Latin calques of the Arabic nomenclature,[54] perhaps deriving from interpolations made in Arabic translations of Ptolemy’s Μαθηματικὴ σύνταξις (the Almagest), from which the first Latin versions of that text were made.[55]

Translating the Fourth Tractate

The present translation is based upon those parts of the Divinum opus especially concerned with astral images and their artificial reproduction, encompassing both practical instructions for their composition and use, and explanations of the principles by which they operate. The first part, largely of a theoretical nature, comes from folios 118r–121r and 127r–130r of Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, MS Plut. 44.35. The remainder, describing the figures, qualities, and powers of images crafted in likeness to (most of) the forty-eight Ptolemaic constellations, as well as a number which are otherwise informed by celestial counterparts, comes primarily from Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Vat. lat. 5333, which I have frequently found to provide more accurate readings of that part of the text than the Florence manuscript does, though I have made emendations based upon Plut. 44.35 in some cases. All of this is part of the fourth tractate of the opus, “On the Methods of Characters, and Their Examples.”

This translation aims to accurately convey to modern English readers the sense of the original text’s often very technical discussions of the theory and practice of astrological image magic….

Endnotes

[1] See Klaassen, 2013: 23–6. On the translation of texts from Islamicate Spain, a primary vector for the transmission of these sources, see Burnett, 1992.

[2] Weill-Parot, 2019: 256.

[3] See Walker, 2000: 12–14 and infra, for a synopsis.

[4] See Shumaker, ed. and trans., 1978.

[5] Cox, 2005: 3–4; Thorndike, 1934: 243.

[6] Agrippa, in a letter to Trithemius justifying the study of magic and his undertaking to redeem it, writes: “Some writers that I have recently seen promise to speak about magic: Roger Bacon, Robertus Anglicus, Pietro d’Abano, Albertus Magnus, Arnaldus de Villa Nova, Giorgio Anselmi, Picatrix the Spaniard, Cecco d’Ascoli…. However, when they do so it is not without certain delusions, unreliable reasoning, or superstitions that are unworthy of anyone who is honest.” (Purdue, trans., 2021: 7–8).

[7] Cox, 2005: 5; Thorndike, 1934: 243.

[8] Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Vat. lat. 4080.

[9] Milano, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, MS H. 233 inf.

[10] Cox, 2005: 5–7.

[11] Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, MS Plut. 44.35.

[12] Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Vat. lat. 5333.

[13] See Aristotle, Physics II.3, and Ptolemy, Tetrabiblos I.2. For Ptolemy’s doctrine especially concerning astrological causes of general phenomena, see Tetrabiblos II; on the Medieval reception of certain elements of this doctrine, see Bezza, 2015.

[14] Plut. 44.35, 118v.

[15] Plut. 44.35, 118r–v, 119v.

[16] Weill-Parot, 2019: 256–7.

[17] Albertus, Book of Minerals II.i.4; see Wyckoff, trans., 1967: 65.

[18] See Tomlinson, 1993: 75–7. This arithmosophic cosmology can be traced directly to Plato’s Timaeus 35–36b, and likely reflects prior Pythagorean doctrines.

[19] Cox, 2005: 23–4. Contrary to Aristotelians like Anselmi (following, for instance, On the Heavens I.3, II.7), other traditions espoused various theories concerning the material composition of the heavens; see, e.g., Macrobius, Commentary on the Dream of Scipio I.xi.8.

[20] Plut. 44.35, 127v.

[21] Plut. 44.35, 129r–v.

[22] See Zambelli, 1992: 54–9.

[23] Burnett et al., trans., 1992: 221.

[24] Wolfson, 1962: 67; see Aristotle, Metaphysics XII.8.

[25] Wolfson, 1962: 68; see Aristotle, On the Heavens II.2.

[26] Wolfson, 1962: 87–9; Zambelli, 1992: 92–4.

[27] Page, 2019: 236.

[28] Page, 2019: 241.

[29] Plut. 44.35, 1r, 121v.

[30] Plut. 44.35, 47r–v: “…those directed by the nature and quality of the fixed stars to move those things and contingencies which the stars themselves govern…”.

[31] See, e.g., Vat. lat. 5333, 10r.

[32] E.g., Vat. lat. 5333, 21r.

[33] Vat. lat. 5333, 26r–v.

[34] Compare, e.g., Vat. lat. 5333, 1v and 10v.

[35] Vat. lat. 5333, 1r.

[36] Cox, 2005: 25.

[37] Burnett et al., trans., 1992: 247.

[38] Burnett et al., trans., 1992: 271. Namely: “In generation and corruption earthly forms are subordinate to the celestials; wherefore they that frame images, do then make use of them, by observing when the planets do enter into those constellations or forms.” (Houlding, ed., 2006, https://www.skyscript.co.uk/centiloquium1.html).

[39] Zambelli, 1992: 296–7.

[40] Plut. 44.35, 118v–119r.

[41] See Weill-Parot, 2012.

[42] Plut. 44.35, 119r. For examples of such prescribed speech, see “Chapter Four: On the Methods of Composing Images Which Are Not Stellar, But Accompany the Twelve Signs”. This again recalls the theory expounded in al-Kindi’s De radiis, e.g. “And among all forms of speech, the optative has greater efficacy, inasmuch as desire indicates the words’ significance and from desire proceeds their natural existence, and therefore their rays effect motion in competent matter greater than other species of rays.” (Gosnell, trans., 2022: 67–8).

[43] See Vat. lat. 5333, 31r.

[44] Burnett, 1996: 66.

[45] I have referred to the edition by Carmody, 1960, and that of Bohak and Burnett, 2021.

[46] See the examples in “Chapter One: On the Images Which Are Made According to the Twelve Signs of the Zodiac.”

[47] Plut. 44.35, 120v–121r.

[48] Bohak and Burnett, eds., 2021: 122, 152.

[49] Bohak and Burnett, eds., 2021: 37.

[50] Juste, 2023b, https://ptolemaeus.badw.de/work/64.

[51] See Bohak and Burnett, eds., 2021: 35–6, 181–9.

[52] Vat. lat. 5333, 29r ff.

[53] See Juste, 2023, https://ptolemaeus.badw.de/work/4.

[54] See in particular “Chapter Two: A Note on the Methods of Composing the Images of the Eighth Sphere That Lie North of the Zodiac” and “Chapter Three: A Note on the Methods Pertaining to Those Images Made Under the Stars of Those Figures Which Occupy the Region South of the Zodiac”.

[55] The earliest known Latin translation of the Almagest was Gerard of Cremona’s, in the latter half of the twelfth century; see Zieme, 2023: 4. Other Arabic works combining Ptolemaic and Arabic star nomenclature, such as the Șuwar al-Kawākib or “Book of the Fixed Stars” of al-Sufi, were also known to the Latin Renaissance; see Hafez, 2010: 249–251, and Kunitzsch, 1987.

About the Author

Brian Johnson is a freelance writer, translator, humanities scholar, and editor. His personal research is largely concerned with reconstructing the esoteric worldviews and practices of historical individuals, based upon the study of primary source documents.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.