Announcing...

The arrival of the folkböcker to Scandinavia in the mid-seventeenth century not only spread magical knowledge and techniques of practices from the Continent, they began to change the way that traditional Scandinavian folk sorcery itself was transmitted, organised, and studied. Such material had previously been almost exclusively orally transmitted, until klokfolk (‘wise ones’) increasingly began writing their instructions, incantations and formularies down in collected books. Some of these collections of recipes, lore, spells, and charms began to be called svartkonstböcker – literally ‘books of the black arts’. In the popular consciousness of the English-speaking world, hardly anything is known about them.

As one of the creators and editors of Revelore Press’ Folk Necromancy in Transmission series, it is both my responsibility and my considerable excitement to announce our forthcoming publication of Dr Thomas K. Johnson’s Svartkonstböcker: A Compendium of the Swedish Black Arts Book Tradition. Based on Dr Johnson’s doctoral thesis, this voluminous work of reference and analysis is not only the most comprehensive work on svartkonstböcker to date, it is also a commemorative offering being published posthumously in honour of the author’s achievements.

And these achievements are worth going over. In addition to providing complete archive records and translations, this tome contains full English translations of no less than thirty-five manuscripts: the largest corpus of Swedish ‘Black Art’ books ever assembled in one study.

Through such detailed analysis of actual primary source manuscripts, Johnson offers vital perspective on both procedural traits and functional intents of the magical operations contained therein. The accompanying detailed commentary ensures such translations can also be of use and interest to an international academic readership. By providing and contextualising these exhaustive source materials, Dr. Johnson has made conclusions that have not previously been possible. He draws attention, for instance, to the points where oral narratives of folk belief about the books deviate from what is represented by the books themselves. As such, this work is able to present the Swedish black art book in richer, more heterogenous detail than ever before.

Rather than simply throwing the reader into a deep end of academia, Johnson carefully introduces the relevant Swedish terminology, leading readers through to a study of the compilers and owners of such black books (the klokfolk) based once more in unedited archival materials. From here he explores folk beliefs about the magic of the black books themselves, before providing detailed notes on each of the manuscripts and their translations.

While Dr. Johnson hoped this volume would afford no small amount of pleasure in the reading, he also hoped that the scholar will find in it a reliable source of Swedish folk narrative in both the original Swedish as well as in English translation, and that the translations of the manuscripts will serve in the future study of international traditions of charms, charming, and folk grimoires. As his widower, Willow communicated to us, ‘Tom was concerned about all these source materials literally rotting in libraries and peoples’ homes. He wanted to do justice to the legacy of his ancestors.’ We are honoured to be a part of this ongoing wish.

What personally excites about this compendium are the veins of Cyprianic magic to be explored in the Swedish ‘black art’ books. As explored in Cypriana: Old World, our first Folk Necromancy in Transmission anthology, legends of Saint Cyprian and his own book(s) of black magic traveled widely across Europe, and represent a fascinating nexus of Christian and pagan practices, not to mention some fairly expressly necromantic formulary. Permit me one brief foray into the kind of material we are talking about.

One manuscript in our upcoming publication (MS 12 NM 40.034) contains the Cypranis Konster och liiror och des inrat (‘The Arts and Teachings of St. Cyprian and its equipment’), which presents an operation to break an enchantment through a ritual enacting of death that takes a particularly blunt but unthreatening manner:

A person who is enchanted should go on a Sunday morning on an empty stomach and silently under an [abul], cut up a turf and put it on his head, and then go three times around the [apulen] and say these words: ‘If I am enchanted and must wait until I go into the earth, then now I have earth both under me and above me and await healing now, in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost’. Recite that three times and put the turf in its place again and go home again, and don’t look back.

Other operations include conjurations of Elemental Kings, at least one operation ‘to perceive if the butter has been bewitched’, instructions in the proper preparation of a divining rod, how to use a cat’s skull in a magical working ‘to have female companionship at night’, and many, many more works of protection, cursing, exorcism, and healing.

Since Revelore Press formally acquired the rights to Dr Johnson’s thesis, we have wanted to release an edition that honours both the ‘black art’ book tradition and Thomas’ considerable contribution to this field. We wish to make this substantial reference work into a beautifully typeset book that stands – in both limited-edition hardback and trade paperback – proudly on the shelf.

Most importantly, however, we feel it essential that this publication honour the wishes of Dr Johnson himself, as well as his nearest and dearest surviving family. As such, we are working closely with his widower (depicted left, at their wedding) to ensure this posthumous celebration of this work is something that not only transmits but expands Thomas’ love and care for his field, that can be guide to this area for others to explore, and an invaluable resource in understanding the particular terroir of this Swedish folk magical book tradition.

Pre-order will open at the Summer Solstice.

Conversing with the Plants: Becky Beyer on foraging, folk magic, and more

~

Meet Becky Beyer, is a farmer, woodcarver, herbalist, witch, and illustrator from Asheville, NC. I met her at Viridis Genii Symposium last year, where she both spoke and played in her musical group Kith and Kin. Becky bridges the worlds between academia (working towards her PhD in Ethnobotany) and Appalachia (teaching in the Primitive Skills community for the last five years). In this interview we discuss her various pursuits and passions in the world of plantlore.

~

Casandra: Thanks for taking the time to talk, Becky. I was happy to hear you present at the Viridis Genii Symposium last year and really impressed by your ability to weave together academic discourse, folk tradition, and personal experience. How did your relationship with the plants begin? Was there an experience that initially impacted you?

Becky: I think for me my relationship with plants began when I got sick with chronic mono—well, that’s what I called it. I had terrible fatigue and a hacking cough for almost a year. I saw six different doctors and they all just didn’t know what to do with me. I ended up visiting a local herb store in Vermont where I was living at the time and the woman there gave me goldenseal, thyme, and boneset. I drank these as a tea for three days, and my cough went away. After a year of struggling with it, I was in tears with joy. I realized then the incredible power of plants, and I started studying them right away. I changed my major in college from Medieval Studies to Plant and Soil Science. It radically shifted my life path.

C: I love hearing stories about the healing capacity of plants; it sounds like that really altered your course! We all relate to the world around us in unique ways; what does relating to plants look like for you?

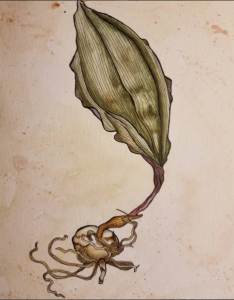

B: For me relating to plants is my living, my passion, and my obsession. I do not relate to plants in the same way as a lot of my colleagues and peers, but I eat wild plants and plants that I grow everyday, and I make my living from them. I am a professional forager and teach people how to forage as my day job. I also sell my art as a botanical illustrator and teach ethnobotany at a local college. I have a spiritual practice that centers around certain plants, but there are other plants that I eat everyday or work with everyday. We have moved into old-friend territory. Rather than making offerings and much ceremony over every plant I pick, I have moved into a relationship where large cyclical offerings have taken the place of that practice. I wonder what my ancestors would have done; the practice of seasonal devotion is the best guess I have.

C: We each have different qualities and types of relationships with the people in our lives. Do you find this to be true with plants as well? Is there a plant that you work with and relate to in a particularly poignant way?

B: I have a handful of plants that excite me and call to me. I love my local Appalachian flora and their incredible histories and magics, specifically Pokeroot, Mayapple, and Sassafras. They are uniquely native, food, medicine, poison, and magic. I love that intersection of “what can cure can also kill” as well as the historical importance of these plants to Native peoples, hoodoo practitioners, and Appalachian folk practitioners.

C: I’m really curious about Appalachian plants specifically and the history of tending stands of wild plants, as well as the songs that folks in that bioregion use in their practice.

B: Growing and tending wild plants here in Appalachia is a complicated thing. Appalachians are used to conversely being romanticized and stereotyped as people who are both in touch with the land, and wanton destructors of nature in reference to mountain top removal and logging. It’s tough. We have incredible local folks with intact knowledge of the uses of hundreds of plants, and those whose only access to resources for making a living is by exploiting the environment.

Ginseng is the biggest cash crop from these mountains other than timber, and the way most people harvest it is to just take every single root they can find. Certain people tend stands on their land only to have them stolen in the night. Others protect certain areas for years only to pass away and have relatives remove all the plants. However, many people grow and cultivate wild plants or tend existing stands regardless.

As far as songs go, we have a lot of traditional songs here for working, but not many specific to picking wild plants. I am sure many people have family songs that were passed down that people sing as they foraged, but because not many do anymore, it’s hard to say. We are creating new traditions and songs for plants; hopefully someday we’ll get around to recording them to share with everyone. As a person of British Isle ancestry, I use the Carmina Gadelica for magical inspiration, and I’ve used the Yarrow charm and others to sing to the plants while I make their medicine. Here is the Yarrow Charm gathered in 1900 in Scots Gaelic:

I WILL pluck the yarrow fair,

That more benign shall be my face,

That more warm shall be my lips,

That more chaste shall be my speech,

Be my speech the beams of the sun,

Be my lips the sap of the strawberry.

May I be an isle in the sea,

May I be a hill on the shore,

May I be a star in waning of the moon,

May I be a staff to the weak,

Wound can I every man,

Wound can no man me.

C: That’s beautiful, thank you for sharing it. We are doing work here in the Northwest to create new traditions around plants and music as well; it seems like such an important aspect of those relationships. How do the plants influence your work as a magical practitioner and teacher?

B: Plants are the backbone of my practice and my work. Sharing and learning their histories and stories is my bread and butter, most literally. I like to focus my teaching about foraging and crafting on how to really work with a plant from a holistic perspective. Plants influence me with their bizarre actions, magical effects, and intoxicating dreamscapes. I work with them by eating them, using them for medicine, and often just by being in their presence or using their energy to aid in a working or make a charm. In Appalachian folk medicine and magic, sometimes just having the plant around, whether around your doorway or in a sachet, is enough to draw on its power. This is how I operate in their realm, and I am always listening, waiting for further instruction.

C: Do you have any advice or favorite resources to share with folks who are perhaps just beginning their work with plants on this relational level?

B: I would recommend my site, Appalachian Ethnobotany. It is a living database of resources on all kinds of plant uses and lore. I just added a folk magic section as well. This is a good place to start. Also, if you are not in Appalachia, reach out to local herbalists, older folks, primitive skills instructors, or anyone else deeply rooted in your bioregion. These are the people to learn from!

C: Well Becky, thank you so much for your time. I love the work you are doing—your art especially—and hope to continue seeing more of it in the herbal, magical, and rewilding circles.

~

If you want to learn more about Becky’s work, writing, music, and magic, check out her article in Verdant Gnosis Vol. 3 on Pokeroot, Mayapple, and Sassafras, as well as her Appalachian Ethnobotany site and her blog www.bloodandspicebush.com.

Also, the Viridis Genii Symposium, where I met Becky, is accepting submissions for their 4th annual event. Make sure to apply by November 28, 2017.

http://www.viridisgenii.com/presenter-proposals/