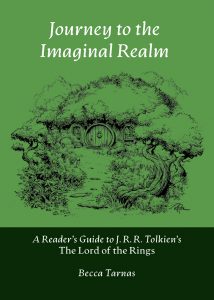

Journey to the Imaginal Realm with Becca Tarnas

The second volume of the Nuralogical series, Journey to the Imaginal Realm by Becca Tarnas, is launching into the world this September 22, 2019. And starting September 29, join Dr Tarnas for an extended, guided journey through Middle-earth at Nura Learning.

The second volume of the Nuralogical series, Journey to the Imaginal Realm by Becca Tarnas, is launching into the world this September 22, 2019. And starting September 29, join Dr Tarnas for an extended, guided journey through Middle-earth at Nura Learning.

In this book, journey into the world of Middle-earth, explore the grand themes and hidden nuances of J. R. R. Tolkien’s epic story, see The Lord of the Rings in the context of the larger mythology of Middle-earth, and delve into Tolkien’s writing process and his powerful experiences of the imaginal realm.

Beloved to several generations since its mid-1950s debut, The Lord of the Rings is a timeless story, engaging with a complex struggle between good and evil, death and immortality, power and freedom. Many treat The Lord of the Rings as a sacred text, returning to it year after year, or reading it aloud with loved ones. The Lord of the Rings has become a myth for our time.

In Journey to the Imaginal Realm, Becca Tarnas guides you through each chapter of Tolkien’s magnum opus, drawing attention to subtle details, recalling moments of foreshadowing, and illuminating underlying patterns and narrative threads. Her close reading of the text is paired with relevant biographical information from Tolkien’s life. Journey to the Imaginal Realm is a celebration of Tolkien’s work, and an inquiry into the profound nature of an imagination capable of bringing forth a world as vast as Middle-earth.

Comprised of six main chapters with several interludes and an in-depth biographical introduction, Tarnas's book canvases the landscape of Tolkien's legendarium, accompanied by six newly commissioned illustrations by Arik Roper.

Please enjoy this excerpt and pre-order your copy of Becca's book today!

Interlude:

Sub-creation: Tolkien’s Philosophy of Imagination

Before continuing with the story in Book II, I wish first to explore J. R. R. Tolkien’s own understanding of his creative process. Tolkien developed a theory of imagination that he called “Sub-creation” as a way to understand the origin and creation of his stories, which he explicated in his essay “On Fairy-Stories.” Tolkien defines “Imagination” as “the faculty of conceiving images,” and “the mental power of image-making.”1 Yet he points out that over time the term “Imagination” has come to mean something more than the faculty of image-making. The term carries a greater potency: “the power of giving to ideal creations the inner consistency of reality.”2 Tolkien is alluding to the English Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and his discussion of the primary and secondary imagination as expressed in Coleridge’s book Biographia Literaria. Coleridge delineates the primary imagination from the secondary imagination as a difference in degree, but not a difference in kind.

Coleridge defined the primary imagination as follows: “The primary Imagination I hold to be the living power and prime agent of all human perception, and as a repetition in the finite mind of the eternal act of creation in the infinite I AM.”3 Coleridge is saying that the primary imagination creates the world we perceive, and shapes our very perception of it. The primary imagination gives to “ideal creations the inner consistency of reality,” as Tolkien puts it. The primary imagination is the source of all images, the wellspring of creativity.

In Biographia Literaria Coleridge also delineates the secondary imagination, which he considers to be an “echo” of the primary imagination. Coleridge says that the secondary imagination is “co-existing with the conscious will, yet still as identical with the primary in the kind of its agency, and differing only in degree, and in the mode of its operation. It dissolves, diffuses, dissipates, in order to recreate.”4 The secondary imagination is the creative will of the human being, which takes the primary source of images and shapes it into art, bringing forth new form. Tolkien’s theory of sub-creation echoes Coleridge’s definitions of the primary and secondary imagination, although it is important to note that Tolkien chooses different terms for his concepts. Sub-creation is essentially a process in two primary stages: the experience of images arising through the “Imagination,” and then the “Art” of shaping those images into the final result. Tolkien calls the final result “Sub-creative Art.”5 The two stages are “Imagination” and then “Art,” and the result is a “Sub-creation.” Yet Tolkien wanted another word that could simultaneously encompass this “Sub-creative Art” and also what he called that “quality of strangeness and wonder in the Expression, derived from the Image.”6 For this word, a word that could encompass all those qualities, Tolkien chose the term “Fantasy.”7

The word “Fantasy” has a wide range of meanings for Tolkien. From his perspective, Fantasy is “the making or glimpsing of Other-worlds.”8 Fantasy is both an activity and the result of that activity. Fantasy is the capacity to create, but also to perceive, an otherworld; and it encompasses the full sensory experience of that otherworld. As Tolkien writes: “Fantasy is a natural human activity. It certainly does not destroy or even insult Reason; and it does not either blunt the appetite for, nor obscure the perception of, scientific verity.”9 Tolkien is careful to differentiate fantasy from dreaming, and to distinguish it also from delusion, hallucination, and mental disorders: “Fantasy is a rational not an irrational activity.”10 Fantasy requires conscious engagement and control by means of the human will. And, as I mentioned previously, fantasy is also the word Tolkien chose to encompass what he meant by “Sub-creative Art.” Thus “Fantasy” is a noun, an adjective, and a verb in Tolkien’s vocabulary, and encompasses the full experience of “making or glimpsing Other-worlds.”

According to Tolkien, a successful sub-creator “makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is ‘true’: it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside.”11 Tolkien calls this occurrence “Secondary Belief.”12 Secondary belief is what we experience when we read a great story, a story such as The Lord of the Rings. We are able to enter into the world of Middle-earth. When one enters a secondary world, and the inner laws of that world are consistent, it feels as though one is truly in that place, seeing the landscapes, hearing the people speaking and interacting with one another, and witnessing events unfold through one’s internal sensory perceptions. A true secondary world echoes the primary world in its expression of reality.

From Tolkien’s perspective, there is yet another level of secondary belief. When secondary belief reaches its most actualized form, then one experiences “Enchantment.” Tolkien writes: “Enchantment produces a Secondary World into which both designer and spectator can enter, to the satisfaction of their senses while they are inside; but in its purity it is artistic in desire and purpose.”13 Enchantment allows one to be fully immersed in a secondary world, beyond any doubt in its reality. Enchantment is what Frodo experiences in the first chapter of Book II, in the Hall of Fire when he hears the Elvish music and visions begin to unfold before him.14 He knows the story being told even though he does not understand all the Elvish words. That is an experience of enchantment, or what Tolkien also at times calls a Faërian Drama.15

Tolkien only uses the term Faërian Drama in a few places, in the essay “On Fairy-Stories” and in his unfinished tale The Notion Club Papers that he wrote in the early 1940s. But the term seems to indicate a kind of visionary experience, or what Tolkien would call a “waking dream.”16 Tolkien is elusive in the way that he speaks about Faërian Drama and Elvish Enchantment, never quite committing to saying this is something that can occur in the real world. Tolkien presents Faërian Drama as a real experience, but he speaks of Elves and the realm of Faërie in a dual and even contradictory way, sometimes as though Elves are real and Faërie an actual place, other times as though they are merely the invention of the human imagination, existing only in a realm of unreality.17 In a few different essays and commentaries, the scholar Verlyn Flieger has engaged with Tolkien’s most contradictory and paradoxical statements in “On Fairy-Stories,” drawing not only on his published text, but on the earlier manuscript drafts of the essay as well. Flieger notes: “Anticipating a skeptical reception, Tolkien tries in the essay as in his letters to have it both ways, on the one hand treating elves as real beings independent of humanity, and on the other hand saying that they are products of human imagination.”18 He is never clear where he stands, expressing the ambiguity of his position in the modern era. In the modernity of Tolkien’s time, secular disenchantment and religious tradition stood as pillars of a world view undergoing deep transformation.

Tolkien uses the term “Sub-creation” because, as a devout Catholic, Tolkien saw himself and other artists and authors as creators under God. Such artists are not the instigators of primary Creation, but rather instruments through whom the divine imagination can be channeled and shaped. Tolkien illustrates this idea in a series of lines from his poem Mythopoeia:

Man, Sub-creator, the refracted Light

through whom is splintered from a single White

to many hues, and endlessly combined

in living shapes that move from mind to mind.19

The human being is able to refract and reshape the divine inspiration into art and creative works, which then continue to refract as others participate in that art. Our reading of The Lord of the Rings, and our experience of seeing the images that arise when we engage in the story, are such a creative participation. We are each prisms, shaping the light of God into an iridescent infinity of sub-creations. Yet those sub-creations also contain within them the primal creative white light of God, the source of the primary imagination.

Tolkien said that literature might be the best medium for sub-creation because of its ability to evoke images directly from the imagination of the reader. The written or spoken word can communicate a universal and a particular simultaneously.20 The word is both concrete and fluid, and leaps from imagination to imagination. As Tolkien eloquently explicates:

Literature works from mind to mind and is thus more progenitive. It is at once more universal and more poignantly particular. If it speaks of bread or wine or stone or tree, it appeals to the whole of these things, to their ideas; yet each hearer will give to them a peculiar personal embodiment in his imagination. . . . If a story says “he climbed a hill and saw a river in the valley below,” the illustrator may catch, or nearly catch, his own vision of such a scene; but every hearer of the words will have his own picture, and it will be made out of all the hills and rivers and dales he has ever seen, but especially out of The Hill, The River, The Valley which were for him the first embodiment of the word.21

One can hear the archetypal to which Tolkien is speaking in this passage: The Hill, The River, The Valley are all capitalized in that final sentence. The written word is able to communicate not only the particular images as they arise in the imagination of the author, but it also connects to the universal or the archetype behind that unique image. The image communicated thus has both a quality of being ancient or even eternal, but also of being newly made or perceived in that moment.

About the author

Becca Tarnas, phd, is a scholar, artist, and editor of Archai: The Journal of Archetypal Cosmology. She received her doctorate in Philosophy and Religion from the California Institute of Integral Studies. Her research interests include depth psychology, literature, philosophy, and the ecological imagination. She teaches in the Jungian Psychology and Archetypal Studies program at Pacifica Graduate Institute, and for online platforms such as Nura Learning, PsicoCymática, and the Astrology Hub. Becca lives in Nevada City, California.

Pre-order your copy of Journey to the Imaginal Realm today!

Notes:

1 Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories, 59.

2 Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories, 59.

3 Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Biographia Literaria (London: J.M. Dent & Co., 1906), 159–60.

4 Coleridge, Biographia Literaria, 159.

5 Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories, 59.

6 Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories, 60.

7 Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories, 60.

8 Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories, 55.

9 Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories, 65.

10 Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories, 60, n. 2.

11 Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories, 52.

12 Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories, 64.

13 Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories, 64.

14 Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring, II, i, 227.

15 Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories, 63; Tolkien, “The Notion Club Papers,” 193.

16 Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring, I, iii, 81.

17 Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories, 32.

18 Verlyn Flieger, “But What Did He Really Mean?” Tolkien Studies 11 (2014): 155.

19 Tolkien, On Fairy Stories, 65.

20 Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories, 61.

21 Tolkien, On Fairy-Stories, 82, n. E.

Journey to the Imaginal Realm

Announcing...

As the curator of philosophies at Revelore, I am pleased to announce the forthcoming publication of Journey to the Imaginal Realm: A Reader's Guide to J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings by Dr. Becca S. Tarnas. Stay tuned for release date announcements in the near future!

Journey to the Imaginal Realm

This reader’s guide to J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Ringsoffers a journey into the world of Middle-earth, exploring the grand themes and hidden nuances of Tolkien’s epic story, connecting The Lord of the Rings to the larger mythology of Middle-earth, and situating Tolkien’s process of writing within his own powerful experiences of the imaginal realm. The Lord of the Ringshas been a beloved story to several generations since its publication in the mid-1950s. The timeless story engages with a complex struggle between good and evil, death and immortality, power and freedom. The Lord of the Ringsis a book treated by many as a sacred text, one to be returned to year after year, or read aloud with loved ones. The Lord of the Ringshas become a myth for our time.

Journey to the Imaginal Realm guides the reader through each chapter of J.R.R. Tolkien’s magnum opus, drawing attention to the subtle details, recalling moments of foreshadowing, and illuminating underlying patterns and narrative threads throughout the story. Close reading of the text is paired with relevant biographical information from Tolkien’s life, including the loss of both his parents at a young age, the central role of friendship in his life, his participation in the First World War, and his exquisite romance with his wife Edith. Tolkien was a lover of language and a philologist by profession, and his invented languages form the heart of his tales. In some of his letters, Tolkien described his process of writing as one of discovery, in which he waited to find out “what really happened,” feeling as though he was “recording what was already ‘there,’ somewhere.” This reader’s guide seeks to understand the imaginal experiences Tolkien may have encountered that led to the writing of his stories. The guide explores Tolkien’s theory of sub-creation, the immersive experience of Faërian Dramas, and most importantly, his notion of the realm of Faërie. Journey to the Imaginal Realm is a celebration of Tolkien’s work, and an inquiry into the profound nature of imagination, which is capable of bringing forth a world as vast as Middle-earth.

Becca S. Tarnas, PhD, is a scholar, artist, and editor of Archai: The Journal of Archetypal Cosmology. She received her doctorate in Philosophy and Religion from the California Institute of Integral Studies, with her dissertation titledThe Back of Beyond: The Red Books of C.G. Jung and J.R.R. Tolkien. Becca received her BA from Mount Holyoke College in Environmental Studies and Theatre Arts, and MA in Philosophy, Cosmology, and Consciousness at CIIS. Her research interests include depth psychology, literature, philosophy, and the ecological imagination. She is currently teaching as an adjunct professor at Pacifica Graduate Institute. Portrait by In Her Image Photography.

Becca S. Tarnas, PhD, is a scholar, artist, and editor of Archai: The Journal of Archetypal Cosmology. She received her doctorate in Philosophy and Religion from the California Institute of Integral Studies, with her dissertation titledThe Back of Beyond: The Red Books of C.G. Jung and J.R.R. Tolkien. Becca received her BA from Mount Holyoke College in Environmental Studies and Theatre Arts, and MA in Philosophy, Cosmology, and Consciousness at CIIS. Her research interests include depth psychology, literature, philosophy, and the ecological imagination. She is currently teaching as an adjunct professor at Pacifica Graduate Institute. Portrait by In Her Image Photography.

Journey to the Imaginal Realm is part of the Nuralogical series created in partnership with course offerings on Nura Learning.

Featured photograph by Constantine Co.

Gebser Society and Seeing Through the World Tote Bags

The bags are in! Revelore was pleased to collaborate with the Gebser Society to produce these tote bags, designed by Jenn Zahrt and featuring an original portrait of Gebser by Nina Bunjavec.

The bags are in! Revelore was pleased to collaborate with the Gebser Society to produce these tote bags, designed by Jenn Zahrt and featuring an original portrait of Gebser by Nina Bunjavec.

These bags were part of a fundraising effort for the Gebser Society after its 2018 conference, "Gebser and Asia" at Naropa University; those who donated at the $100 level receive a tote with a personal note from me (as Gebser Society president). Expect to see them in the mail this holiday season. If you're interested in grabbing a tote for integral sojourning, see the donation page on the Gebser society's homepage.

Revelore is also pleased to be featuring Nina's portrait in the imminent publication of Seeing Through the World: Jean Gebser and Integral Consciousness, the first book in our Philosophies series. Pre-order is opening soon.

Announcing...

The arrival of the folkböcker to Scandinavia in the mid-seventeenth century not only spread magical knowledge and techniques of practices from the Continent, they began to change the way that traditional Scandinavian folk sorcery itself was transmitted, organised, and studied. Such material had previously been almost exclusively orally transmitted, until klokfolk (‘wise ones’) increasingly began writing their instructions, incantations and formularies down in collected books. Some of these collections of recipes, lore, spells, and charms began to be called svartkonstböcker – literally ‘books of the black arts’. In the popular consciousness of the English-speaking world, hardly anything is known about them.

As one of the creators and editors of Revelore Press’ Folk Necromancy in Transmission series, it is both my responsibility and my considerable excitement to announce our forthcoming publication of Dr Thomas K. Johnson’s Svartkonstböcker: A Compendium of the Swedish Black Arts Book Tradition. Based on Dr Johnson’s doctoral thesis, this voluminous work of reference and analysis is not only the most comprehensive work on svartkonstböcker to date, it is also a commemorative offering being published posthumously in honour of the author’s achievements.

And these achievements are worth going over. In addition to providing complete archive records and translations, this tome contains full English translations of no less than thirty-five manuscripts: the largest corpus of Swedish ‘Black Art’ books ever assembled in one study.

Through such detailed analysis of actual primary source manuscripts, Johnson offers vital perspective on both procedural traits and functional intents of the magical operations contained therein. The accompanying detailed commentary ensures such translations can also be of use and interest to an international academic readership. By providing and contextualising these exhaustive source materials, Dr. Johnson has made conclusions that have not previously been possible. He draws attention, for instance, to the points where oral narratives of folk belief about the books deviate from what is represented by the books themselves. As such, this work is able to present the Swedish black art book in richer, more heterogenous detail than ever before.

Rather than simply throwing the reader into a deep end of academia, Johnson carefully introduces the relevant Swedish terminology, leading readers through to a study of the compilers and owners of such black books (the klokfolk) based once more in unedited archival materials. From here he explores folk beliefs about the magic of the black books themselves, before providing detailed notes on each of the manuscripts and their translations.

While Dr. Johnson hoped this volume would afford no small amount of pleasure in the reading, he also hoped that the scholar will find in it a reliable source of Swedish folk narrative in both the original Swedish as well as in English translation, and that the translations of the manuscripts will serve in the future study of international traditions of charms, charming, and folk grimoires. As his widower, Willow communicated to us, ‘Tom was concerned about all these source materials literally rotting in libraries and peoples’ homes. He wanted to do justice to the legacy of his ancestors.’ We are honoured to be a part of this ongoing wish.

What personally excites about this compendium are the veins of Cyprianic magic to be explored in the Swedish ‘black art’ books. As explored in Cypriana: Old World, our first Folk Necromancy in Transmission anthology, legends of Saint Cyprian and his own book(s) of black magic traveled widely across Europe, and represent a fascinating nexus of Christian and pagan practices, not to mention some fairly expressly necromantic formulary. Permit me one brief foray into the kind of material we are talking about.

One manuscript in our upcoming publication (MS 12 NM 40.034) contains the Cypranis Konster och liiror och des inrat (‘The Arts and Teachings of St. Cyprian and its equipment’), which presents an operation to break an enchantment through a ritual enacting of death that takes a particularly blunt but unthreatening manner:

A person who is enchanted should go on a Sunday morning on an empty stomach and silently under an [abul], cut up a turf and put it on his head, and then go three times around the [apulen] and say these words: ‘If I am enchanted and must wait until I go into the earth, then now I have earth both under me and above me and await healing now, in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost’. Recite that three times and put the turf in its place again and go home again, and don’t look back.

Other operations include conjurations of Elemental Kings, at least one operation ‘to perceive if the butter has been bewitched’, instructions in the proper preparation of a divining rod, how to use a cat’s skull in a magical working ‘to have female companionship at night’, and many, many more works of protection, cursing, exorcism, and healing.

Since Revelore Press formally acquired the rights to Dr Johnson’s thesis, we have wanted to release an edition that honours both the ‘black art’ book tradition and Thomas’ considerable contribution to this field. We wish to make this substantial reference work into a beautifully typeset book that stands – in both limited-edition hardback and trade paperback – proudly on the shelf.

Most importantly, however, we feel it essential that this publication honour the wishes of Dr Johnson himself, as well as his nearest and dearest surviving family. As such, we are working closely with his widower (depicted left, at their wedding) to ensure this posthumous celebration of this work is something that not only transmits but expands Thomas’ love and care for his field, that can be guide to this area for others to explore, and an invaluable resource in understanding the particular terroir of this Swedish folk magical book tradition.

Pre-order will open at the Summer Solstice.

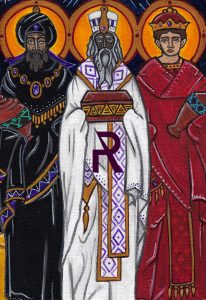

Happy Epiphany, 2018

Happy Epiphany, dear reader.

The sixth day of January has been associated with a variety of significant events in various Christian calendars – the original date of the Christ-child's birth, the baptism of an adult Jesus by John the Baptist in the Jordan, the miracle of the water into wine during the marriage at Cana. But one event has won out into the modern calendars: the Adoration of the Magi. The coming of the Wise-Men, guided by a Star in the East, to honour the born and future King of the Jews, and present their gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. These figures, these foreign Magi who would eventually become known as the Three Kings, came to cohere and inspire a medieval cult that made the eventual resting place of their bones – the Cathedral of Saint Peter in Cologne – one of the major hubs of medieval pilgrimage. And so it is today that I am proud to announce, as both an author and as an editor of Revelore Press' Folk Necromancy in Transmission series, that A Book of the Magi: Lore, Prayers, and Spellcraft of the Three Holy Kings is now available for pre-sale prior to its formal release on the third day of the third month of the year 2018.

The sixth day of January has been associated with a variety of significant events in various Christian calendars – the original date of the Christ-child's birth, the baptism of an adult Jesus by John the Baptist in the Jordan, the miracle of the water into wine during the marriage at Cana. But one event has won out into the modern calendars: the Adoration of the Magi. The coming of the Wise-Men, guided by a Star in the East, to honour the born and future King of the Jews, and present their gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. These figures, these foreign Magi who would eventually become known as the Three Kings, came to cohere and inspire a medieval cult that made the eventual resting place of their bones – the Cathedral of Saint Peter in Cologne – one of the major hubs of medieval pilgrimage. And so it is today that I am proud to announce, as both an author and as an editor of Revelore Press' Folk Necromancy in Transmission series, that A Book of the Magi: Lore, Prayers, and Spellcraft of the Three Holy Kings is now available for pre-sale prior to its formal release on the third day of the third month of the year 2018.

This book explores the history of the Magi from their first literary appearance in the Gospel of Matthew to their earliest depictions in ritual art on sarcophaguses and the walls of catacombs, through to the translated bones of the Three Holy Kings making Cologne one of the most important pilgrimage sites in the medieval world. This popularity leads to the rise of early modern traditions of parades, 'star-singing', begging, and masking. A radical tension is explored between the Magi as both supporting and upending political power structures. On the one hand, they are foreign wise-men legitimising a central authority. Yet they are also powerful, often indigenous, Othered pre-Christian magicians destabilising that authority. This tension is especially apparent in the Three Kings' influence and inspiration throughout colonisation of the so-called "New World".

This book explores the history of the Magi from their first literary appearance in the Gospel of Matthew to their earliest depictions in ritual art on sarcophaguses and the walls of catacombs, through to the translated bones of the Three Holy Kings making Cologne one of the most important pilgrimage sites in the medieval world. This popularity leads to the rise of early modern traditions of parades, 'star-singing', begging, and masking. A radical tension is explored between the Magi as both supporting and upending political power structures. On the one hand, they are foreign wise-men legitimising a central authority. Yet they are also powerful, often indigenous, Othered pre-Christian magicians destabilising that authority. This tension is especially apparent in the Three Kings' influence and inspiration throughout colonisation of the so-called "New World".

Having traced the history of their veneration and mythology, we have context to more fully explore and integrate their appearances in a variety of operations found throughout the grimoiric records of magical handbooks and folk ritual alike: works of travelling, of detection, of conjuration, of dominating supposed superiors, and many more. Along with these operations come a range of prayers and ritual historiolae (appeals to mythic actions or origins, often by imitation), fit for devotional meditation and operative sorcery alike.

These magical workings are further joined by new gifts from myself, which include recipes and operations from my own practice, as well as personal notes and instructions for blessing materia and constructing talismans. There is particular attention paid to ritual design as well as analysis, and on showing rather than merely telling how to pull useful components for developing personal relationships and magical practices from old texts and customs.

Overall, this book approaches the Magi not simply as a set of three more saints to venerate individually, but as a collective folk necromantic loci by which further relations with ancestral magicians of many creeds may cohere and manifest. It is by the light of a Star in the East, charting our way through darkness, that we may be supported in our travels and travails through life by those dead magicians who have come before us.

I write this on Epiphany's Eve in the city of Cologne having journeyed here to pay homage to their relics tomorrow. I have been delighted not only to wander around the Cathedral housing the Three Kings' precious crowned skulls prior to formal Epiphany celebrations, but also to find the house blessing associated with the Wise-Men – a chalked C + M + B formula – adorning many a neighourhood door. The Magi have formed a significant locus in my magical and spiritual practice for a good few years now, and continue to inspire me to explore new occult and theological terrain and perspectives. In recent weeks, as I have prepared for this pilgrimage, I have shared some thoughts on ceremonies leading up to Epiphany, and rites one might partake in to honour the Magi on their Feast. I have been delighted to see that other colleagues and friends have been sharing similarly.

I write this on Epiphany's Eve in the city of Cologne having journeyed here to pay homage to their relics tomorrow. I have been delighted not only to wander around the Cathedral housing the Three Kings' precious crowned skulls prior to formal Epiphany celebrations, but also to find the house blessing associated with the Wise-Men – a chalked C + M + B formula – adorning many a neighourhood door. The Magi have formed a significant locus in my magical and spiritual practice for a good few years now, and continue to inspire me to explore new occult and theological terrain and perspectives. In recent weeks, as I have prepared for this pilgrimage, I have shared some thoughts on ceremonies leading up to Epiphany, and rites one might partake in to honour the Magi on their Feast. I have been delighted to see that other colleagues and friends have been sharing similarly.

And so today marks a celebration, but also an offering whose delivery has been the work of many hands. The research that has gone into my Book of the Magi has been informed by the work of many scholarly authors, but perhaps more immediately it has been the labour of my colleague and publisher Dr Jennifer Zahrt at Revelore Press, the incredibly talented hand and eye of my favourite living icon-painter, S. Aldarnay – who has contributed the inspiring portrait of the Magi that we have made a further gift available to early purchasers of this book – and the support and love of my family. Many, many other people deserve ample recognition and praise – which I have tried to provide in the Acknowledgements fronting A Book of the Magi. It is my hope that if you are one of those fellows reading this now, you already understand the assistance you have so kindly gifted me. Thank you.

It is my hope that this book prompts, arms, and (in at least some small fashion) inspires its readers to seek further engagement with the Three Holy Kings – to travel like pilgrims following a Star, to offer gifts to that which they celebrate as greater than them, and to continue to devote themselves to celebrating Light in Darkness, to rejoicing through their travails, and communing honestly, respectfully, and powerfully with their magician ancestors who came before them. It is far from a definitive work – rather, it hopefully speaks to the immediacy of magical and spiritual action, of setting foot upon the trail, and of continuing on the journey ahead. I hope it brings myself and others into closer communion with both our sorcerous forebears and our companions along the dusty way, and contributes to the treasury of magic that nourishes, fortifies, and illuminates.

It is my hope that this book prompts, arms, and (in at least some small fashion) inspires its readers to seek further engagement with the Three Holy Kings – to travel like pilgrims following a Star, to offer gifts to that which they celebrate as greater than them, and to continue to devote themselves to celebrating Light in Darkness, to rejoicing through their travails, and communing honestly, respectfully, and powerfully with their magician ancestors who came before them. It is far from a definitive work – rather, it hopefully speaks to the immediacy of magical and spiritual action, of setting foot upon the trail, and of continuing on the journey ahead. I hope it brings myself and others into closer communion with both our sorcerous forebears and our companions along the dusty way, and contributes to the treasury of magic that nourishes, fortifies, and illuminates.

And so, I wish you a blessed, happy and healthy Epiphany. If nothing else, I hope you find time to raise a glass to the Magi and to the Star! To the Infant! To the Mother, and to the Father!

Let The Kings Drink!