Conversing with the Plants: Becky Beyer on foraging, folk magic, and more

~

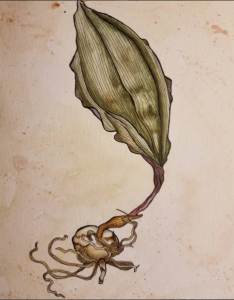

Meet Becky Beyer, is a farmer, woodcarver, herbalist, witch, and illustrator from Asheville, NC. I met her at Viridis Genii Symposium last year, where she both spoke and played in her musical group Kith and Kin. Becky bridges the worlds between academia (working towards her PhD in Ethnobotany) and Appalachia (teaching in the Primitive Skills community for the last five years). In this interview we discuss her various pursuits and passions in the world of plantlore.

~

Casandra: Thanks for taking the time to talk, Becky. I was happy to hear you present at the Viridis Genii Symposium last year and really impressed by your ability to weave together academic discourse, folk tradition, and personal experience. How did your relationship with the plants begin? Was there an experience that initially impacted you?

Becky: I think for me my relationship with plants began when I got sick with chronic mono—well, that’s what I called it. I had terrible fatigue and a hacking cough for almost a year. I saw six different doctors and they all just didn’t know what to do with me. I ended up visiting a local herb store in Vermont where I was living at the time and the woman there gave me goldenseal, thyme, and boneset. I drank these as a tea for three days, and my cough went away. After a year of struggling with it, I was in tears with joy. I realized then the incredible power of plants, and I started studying them right away. I changed my major in college from Medieval Studies to Plant and Soil Science. It radically shifted my life path.

C: I love hearing stories about the healing capacity of plants; it sounds like that really altered your course! We all relate to the world around us in unique ways; what does relating to plants look like for you?

B: For me relating to plants is my living, my passion, and my obsession. I do not relate to plants in the same way as a lot of my colleagues and peers, but I eat wild plants and plants that I grow everyday, and I make my living from them. I am a professional forager and teach people how to forage as my day job. I also sell my art as a botanical illustrator and teach ethnobotany at a local college. I have a spiritual practice that centers around certain plants, but there are other plants that I eat everyday or work with everyday. We have moved into old-friend territory. Rather than making offerings and much ceremony over every plant I pick, I have moved into a relationship where large cyclical offerings have taken the place of that practice. I wonder what my ancestors would have done; the practice of seasonal devotion is the best guess I have.

C: We each have different qualities and types of relationships with the people in our lives. Do you find this to be true with plants as well? Is there a plant that you work with and relate to in a particularly poignant way?

B: I have a handful of plants that excite me and call to me. I love my local Appalachian flora and their incredible histories and magics, specifically Pokeroot, Mayapple, and Sassafras. They are uniquely native, food, medicine, poison, and magic. I love that intersection of “what can cure can also kill” as well as the historical importance of these plants to Native peoples, hoodoo practitioners, and Appalachian folk practitioners.

C: I’m really curious about Appalachian plants specifically and the history of tending stands of wild plants, as well as the songs that folks in that bioregion use in their practice.

B: Growing and tending wild plants here in Appalachia is a complicated thing. Appalachians are used to conversely being romanticized and stereotyped as people who are both in touch with the land, and wanton destructors of nature in reference to mountain top removal and logging. It’s tough. We have incredible local folks with intact knowledge of the uses of hundreds of plants, and those whose only access to resources for making a living is by exploiting the environment.

Ginseng is the biggest cash crop from these mountains other than timber, and the way most people harvest it is to just take every single root they can find. Certain people tend stands on their land only to have them stolen in the night. Others protect certain areas for years only to pass away and have relatives remove all the plants. However, many people grow and cultivate wild plants or tend existing stands regardless.

As far as songs go, we have a lot of traditional songs here for working, but not many specific to picking wild plants. I am sure many people have family songs that were passed down that people sing as they foraged, but because not many do anymore, it’s hard to say. We are creating new traditions and songs for plants; hopefully someday we’ll get around to recording them to share with everyone. As a person of British Isle ancestry, I use the Carmina Gadelica for magical inspiration, and I’ve used the Yarrow charm and others to sing to the plants while I make their medicine. Here is the Yarrow Charm gathered in 1900 in Scots Gaelic:

I WILL pluck the yarrow fair,

That more benign shall be my face,

That more warm shall be my lips,

That more chaste shall be my speech,

Be my speech the beams of the sun,

Be my lips the sap of the strawberry.

May I be an isle in the sea,

May I be a hill on the shore,

May I be a star in waning of the moon,

May I be a staff to the weak,

Wound can I every man,

Wound can no man me.

C: That’s beautiful, thank you for sharing it. We are doing work here in the Northwest to create new traditions around plants and music as well; it seems like such an important aspect of those relationships. How do the plants influence your work as a magical practitioner and teacher?

B: Plants are the backbone of my practice and my work. Sharing and learning their histories and stories is my bread and butter, most literally. I like to focus my teaching about foraging and crafting on how to really work with a plant from a holistic perspective. Plants influence me with their bizarre actions, magical effects, and intoxicating dreamscapes. I work with them by eating them, using them for medicine, and often just by being in their presence or using their energy to aid in a working or make a charm. In Appalachian folk medicine and magic, sometimes just having the plant around, whether around your doorway or in a sachet, is enough to draw on its power. This is how I operate in their realm, and I am always listening, waiting for further instruction.

C: Do you have any advice or favorite resources to share with folks who are perhaps just beginning their work with plants on this relational level?

B: I would recommend my site, Appalachian Ethnobotany. It is a living database of resources on all kinds of plant uses and lore. I just added a folk magic section as well. This is a good place to start. Also, if you are not in Appalachia, reach out to local herbalists, older folks, primitive skills instructors, or anyone else deeply rooted in your bioregion. These are the people to learn from!

C: Well Becky, thank you so much for your time. I love the work you are doing—your art especially—and hope to continue seeing more of it in the herbal, magical, and rewilding circles.

~

If you want to learn more about Becky’s work, writing, music, and magic, check out her article in Verdant Gnosis Vol. 3 on Pokeroot, Mayapple, and Sassafras, as well as her Appalachian Ethnobotany site and her blog www.bloodandspicebush.com.

Also, the Viridis Genii Symposium, where I met Becky, is accepting submissions for their 4th annual event. Make sure to apply by November 28, 2017.